Whole Lot.

Emily Kam Kngwarray. My Country, PACE London, 8 June- 8 August 2025

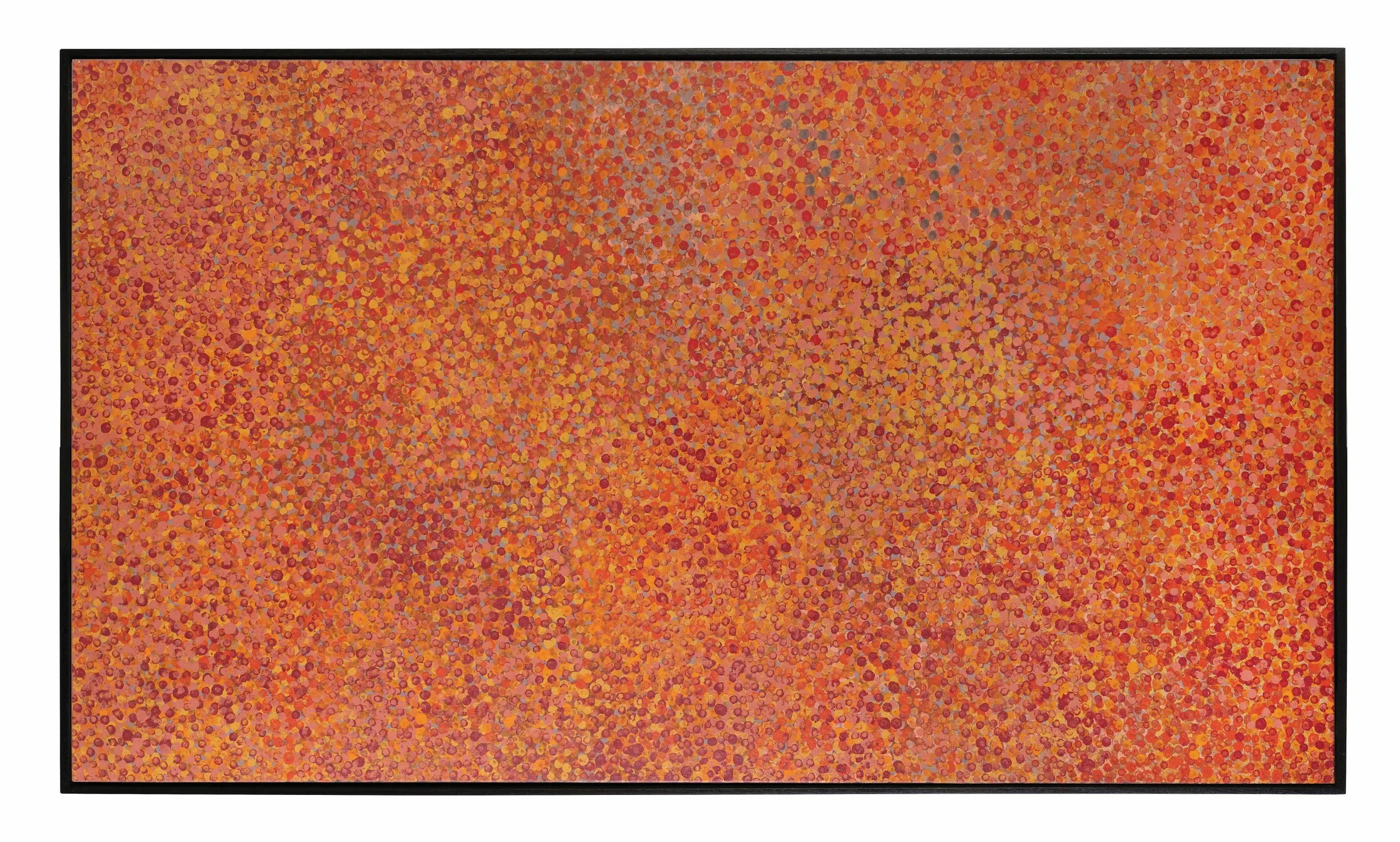

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Desert Storm, 1992, acrylic on canvas, 138.9 cm × 304.8 cm (54-11/16" × 10'), © Emily Kam Kngwarray/Copyright Agency

The paintings fill the space. They affect me the same way living beings do. My Country, Emily Kam Kngwarray’s exhibition at PACE London is simply beautiful. Experiencing it feels like a sensory act of learning, an invitation to be with.

Conceived in collaboration with D’Lan Contemporary and sensitive support from D’Lan’s Head of Research, Vanessa Merlino, to coincide with Kngwarray’s retrospective at Tate Modern, it is a timely and thoughtful show, lovingly putting together a selection of works representative of the artist’s extraordinary practice.

While the main gallery presents paintings on canvas, the lower ground contains selection of batiks, medium of Kngwarray’s choice before her move to painting, and a medium which informed her assured technique later on.

Installation view, Emily Kam Kngwarray: My Country, 6 June-8 August 2025, Pace Gallery, London.

Born in 1910, Emily Kam Kngwarray, was “one of the last generations of Indigenous Elders born and raised before the settlers’ influence impinged” 1.She started to work in painting relatively late in her life, when she was already an Anmatyerr Elder, with first painting on canvas in 1988, when she was in her late seventies. In her short career, she painted a staggering number of over 3000, often completed in a day, works. With a rarely seen mastery.

As an Elder, Kngwarray was keeper of knowledge and co-caretaker of sacred sites. This status within the community informed her way of working in art. To Kngwarray painting, art, was an extension of her life, where cultural identity, ceremony, understanding of land and seasons, stories and songs, are inseparably interwoven in the way of living.

Alhalker, Kngwarray’s home, and its sentient and sensuous land, the cosmos she was an integral part of, is at the very centre of her practice, manifesting in physical, bodily, and spiritual way. Her work is not a representation, but a complete record of the Country, finished in the present moment, emerging during the daily act of painting, where Emily Kam Kngwarray, Alhalker and Altyerr are existing in the now, the before and forever.

Within the Alhalker community “the physical systems of nature are maintained and balanced by the correct performance of ceremonies handed down through the ages by the ancestors. The fertility of the soil, growth of significant food sources, and prospectus seasons following good rains rely on the repeated and ritualised sets of practices of the Dreaming Law.”2.The painting is an extension of this ceremonial character.

Ceremony ensures health and continuity of the community. For Kngwarray, Awely, ceremony performed within female gatherings, where marks (arkeny) are applied onto women’s bodies, and the process is a vehicle of connection and becoming, accompanied by singing, and dance cycles was an anchoring point. Awely informs her pointing as a process of the country painted onto the body and in a way, becoming one with it.

Kngwarray engaged her whole body in her mark-making, she often sang when working on canvas flatly spread on the ground. Her way of working performatively, with daily rhythm and application of multiple layers emerges from her ceremonial bodily and spiritual experience. Canvas positioned in close proximity to the ground, stretcher touching the soil, the song which is the story, mark-making, and presence of female energy, reflect corporeal and spiritual dimensions gained through Awely. This performative, transformative approach to the painting originates in the very same cosmology, which informed the artist’s cultural and spiritual universe.

“Kam, Kngwarray’s middle name, means yam flower or yam seed, conveying her embodiment of the Altyerr for the yam and her authority as a holder of its Law”. 3

Kngwarray’s paintings didn’t come from isolation. They originate in culture grounded and shaped by relationships. They emerge from a way of life based on reciprocity and mutual care. Spread across times and beings, Kngwarray’s Country is a living entity, a community of existences entangled in networks that make it work and last, defined and supported by the Dreaming. It is a way marked by kinship with more than human connection; to us, to the seeds; to the roots, to plants, to animals; binding different ways of understanding that come from connections to beings other than human. The paintings are meant to be shared, communal just as practice of Alhalker life is a shared experience, between the Country-all beings of the land .

Installation view, Emily Kam Kngwarray: My Country, 6 June-8 August 2025, Pace Gallery, London.

The lower ground gallery is dominated by fabric, softness and playability of textile, the tactile presence of the Country marked on each piece. Suspended batiks create a communal place of an encounter, reflecting the communal character of their production. The space is gathering, open to exploration, gathering of presences, gathering of lands, assembly of stories. It is an invitation to join. To stand in a circle, within the land, within the community. Textiles floating in response to our movement feel like a sensory exchange, corporeal choreography. Giving off a sense of generosity, of openness, of shared space. It is impossible to ever see only one piece, they are always in relation. Movement of textile, flow of the air, potentiality of change, discovered as we walk in-between, experiencing sensory proximities of distance and time, batiks make me think of transformation embedded in nature, a culture of interconnectedness.

I think metaphorically this gathering mirrors the gatherings that happened countless times before. There are many gatherings in this exhibition. The gathering of works which are vessels for the spiritual reality of beings that constitute Alhalker Country. The physical and sensorial gathering of batiks in the lower ground gallery and the gathering during their production.. The gathering of women around Emily when she painted. Recalled from memory, past gatherings of women during ceremonies in endless temporalities since the time of ancestors.The gathering of people that make a community. The gathering of beings that make the Country. The gathering of canvases marking Emily practice and life, forever entangled. The gatherings of people who come to be with paintings and in truth end up being with the land. With the Country. The gallery has become a cosmos in the network of living, of spirits, energies and relationships.

“The act of painting is a sacred process, and contributes to the spiritual enhancement of the self.” 4

What is significant about all Kngwarray’s works is their intentionality. All images can be defined as representational in a sense that they become yam roots, the Dreaming, body marks, woman’s body, emu, land, soil, ancestors and so on. I see them as transitional spaces of becoming. They are becoming emu, yam, plants, animals, sky, rocks and land. Always land. The Country. The Whole Lot. They become the cosmos of Kngwarray’s life. Entangled timelines of being.intended to be present through painting and process of art-making.

Pointing process can be seen as corporeal exploration, stretch of an arm, movement of the brush, spine bent over ground, response to canvas, the feel of it lying flat on the ground connected to it though simple stretcher, like soles of our feet on the ground, feeling the soil below. The proximity of the land. It emphasises the real and the sensory, beyond the spiritual connection with the Country. It recalls female bodies, which become the Country during Awely from the moment of gathering and application of the marks by the Elder. The intention behind the work is to transmit Altyerr-the Dreaming, helping the forces in the ground moving and residing through and within the body and manifest them on canvas.

Installation view, Emily Kam Kngwarray: My Country, 6 June-8 August 2025, Pace Gallery, London.

“The rhythmic beating of the brush, dots penetrating the ground underneath the canvas is a vital component in communicating the aliveness of Dreaming. As a keeper of ancestral knowledge, Emily had both a reverence for ceremony and devotional touch that she attained and imparted throughout her life. This became integral in her painting practice, with the rituals and repetitions of her culture being imprinted on her canvases.” 5

The painting is a body covered in marks signifying Dreaming, just like a body of a woman covered in Awely marks going through transformation There is no distinction between painting and Country, just as there is no distinction between transformative ritual, dreaming and Kngwarray’s life. “Each dot indicates the mimetic traces of the ancestors, the land they traversed and the cultural teaching they handed down.” 6

In this sense the ceremony is central to Kngwarray’s work. Paintings are not objects, but expressions of practice. They are an extension of the Country, the ancestors, life defined by connections and custodianship. Practice and ceremony that are ways of being. The artist does not represent her Dreaming. She is her Dreaming. Painting gestures toward the ongoing and reciprocal relationship with the ancestors and the Dreaming, from one generation to the rest.

Land is a sentient being, responsive to its circumstances and creatures living on it. Kngwarray understood her painting practice an extension of caring for the Country and as such, to contribute to the well-being of herself and the place she belonged to. Works (...) literally bring The Dreaming into being. Ancestral potency arises within these paintings and is actively produced by them. 7

Paintings are part of life of unbroken cultural performance, of reverence of the ceremony and intimate relationship with the land. Like in her late works where paint strokes look like a mark applied by hand flat against the body, against the muscle, the skin, changing it, making it become more. It reflects gestural application of designs painted directly onto skin for ceremonial dances and the movement of bodies committed to honouring cultural practices that stretch back to the times of the sacred ancestors.

Paintings were done mostly in a day, with performativity of the ceremony transferred onto the brush. It happened in the now. But also, it traversed time, the time of ancestors; past, present and now together. It is the very practice where art-making is ontologically an act of knowledge production and practice of communication. Where knowing is being and being is knowing.

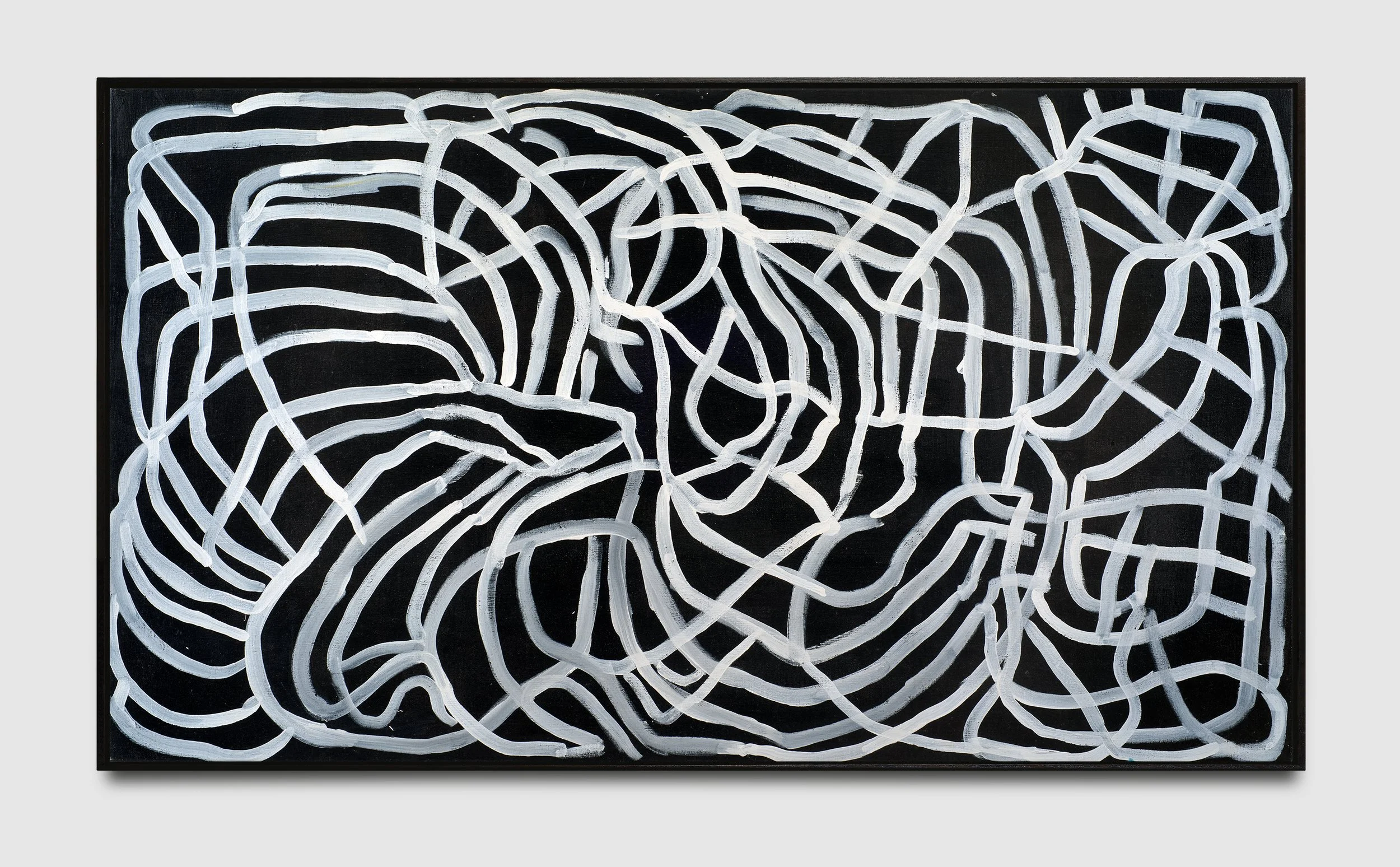

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Alhalker, 1991, acrylic on canvas, 121 cm × 213 cm (47-5/8" × 83-7/8"), © Emily Kam Kngwarray/Copyright Agency

“There is no place without history; there is no place that has not been imaginatively grasped through song, dance and design, no place where traditional owners cannot see the imprint of sacred creation.”8 The Elder has the duty to ensure that botanical, ceremonial, spiritual, and ancestral knowledge is passed down through the generations. This is a culture of intergenerational knowledge.

This process of becoming is embedded in attunement to the country, to daily, seasonal and annual shifts encoded within the canvas, a movement that is an inherent potentiality of change of natural world along and that undermines spiritual and cultural centre of A identity, supported by ceremony, a survival and movement, a potentiality, and again, becoming.

I think of it as cosmology that outlines living as practice of being with. But also becoming something, someone else. The boundaries of beings who together constitute the Country are porous in a similar manner to flexibility of time-lines and co-existences of multiple temporalities which establish the multi-faceted structure of Alhalker cosmos. A cosmos of entangled paths-tracks-energies. A Universe where one consists of many.

It is an art that is the practice (of becoming) where beings, temporalities, time mode and cosmology are connected by umbilical cord of Dreaming (of painting, woman, body and Country).

For me, the Westerner, the idea of land as living, sentient and aware being as opposed to the notion of the objectified landscape that I was raised with, started to take shape years ago after seeing Tarkovsky’s ‘Stalker’ or maybe even earlier after reading Lem’s ‘Solaris’. The concept that land physically, organically changes, purposely altering itself in order to communicate across species held an immense beauty. The notion that we need to change ourselves in order to respond to it, altered my understanding of our position not on the land, but in relation to it, attuned to different forms of communication, to non-human non-verbal language. And seeing this understanding of survival as a connection. And this sort of relationship is intimate and sensory.

I take this sensation, this experience with me, to un-anchor myself from my conditioning and to feel these paintings. However I don't see them as paintings, instead to me they are habitats. They do not represent the Country. They are an extension of it. The paintings are extensions of land, of practice, of life, expressing Kngwarray’s deep reverence for the ancestrally created land, sea and sky.

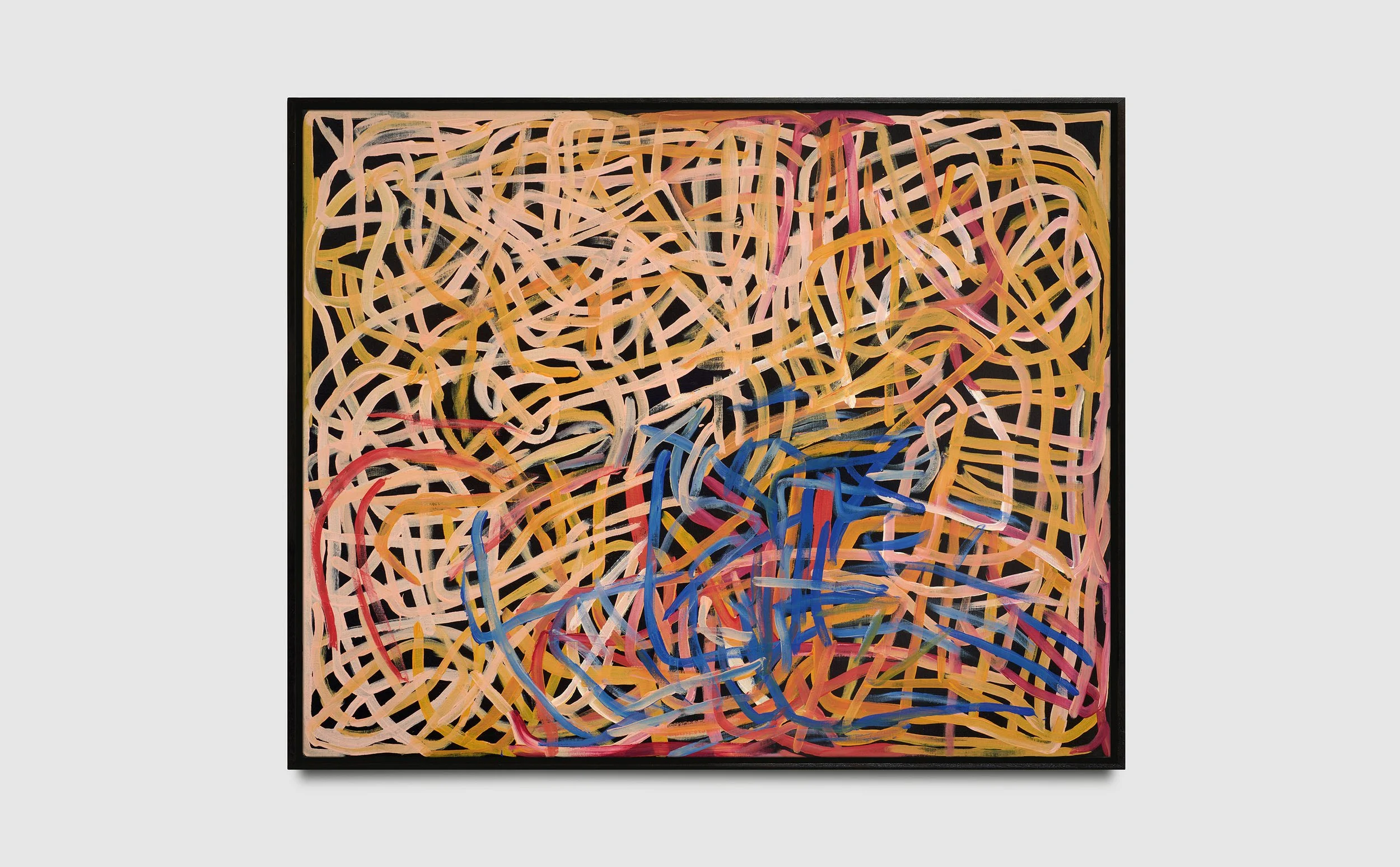

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Anooralya Yam, 1995, acrylic on canvas, 122.6 cm × 212.4 cm (48-1/4" × 83-5/8"), © Emily Kam Kngwarray/Copyright Agency

The paintings chart relationships to people, to place, and to the ancestors who gifted it all. They “are participatory ecosystems that assert a lifetime commitment to the stewardship of cultural memory and to the knowledge and poetics of place.” 9

The process of painting is an extension of practice, culture and life built upon intimacy with the land. Paintings are notations of country-land, woman-body, dreaming-ceremony as they become time-space.

It is a time-mode of life entangled.. It is a shimmering self-portrait as kin.

Maybe Emily’s paintings are so affective because they shimmer. Shimmer with energy of relationships, care, practice and attention. They shimmer with beings, seasons, weather changes, old times lasting in the new, dry country’s soil, bird flight, wind or stars. They shimmer with life and all its complexity.

The paintings radiate the purpose of being. These are transmissions of lived experience. Their performativity lies in the experiential character and intended open nature. What affects me the most, even despite their lyrical beauty, is the fact that they shift my culturally conditioned understanding of the world.

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Yam Roots, 1996, acrylic on canvas, 122 cm × 152 cm (48-1/16" × 59-13/16"), © Emily Kam Kngwarray/Copyright Agency

“Whole lot, that’s whole lot, Awely (my Dreaming), Anwelarr (pencil yam), Arkerrth (mountain devil lizard), Ntan (grass seed), Tingu (a Dream-time pup), Ankerr (emu), Intekw (a favourite food of emus, a small plant), Atnwerl (green bean), and Kam (yam seed). That’s what I paint: a whole lot…”

Emily Kam Kngwarray 10

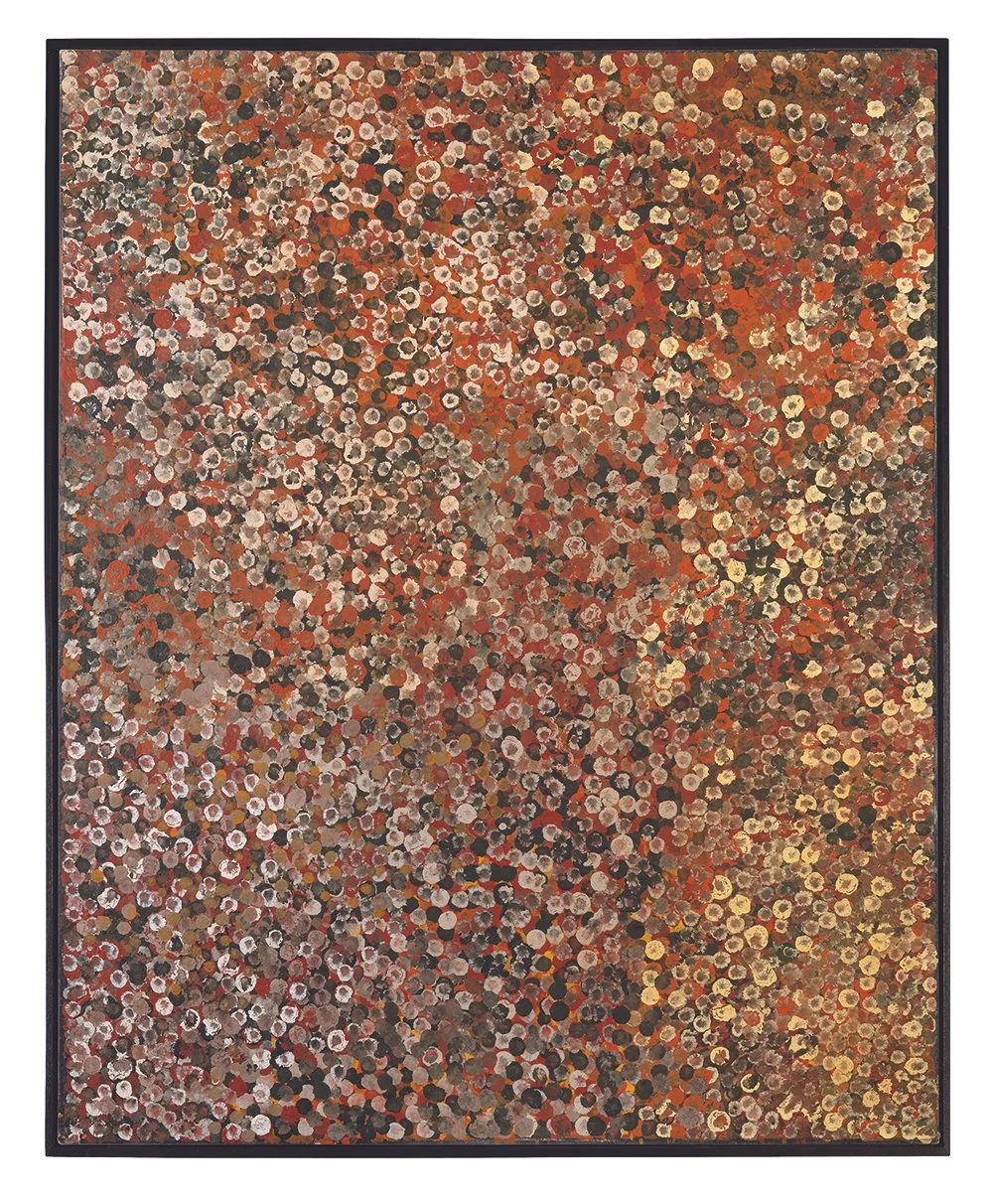

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Transition, 1990, acrylic on canvas, 150 cm × 120 cm (59-1/16" × 47-1/4"), © Emily Kam Kngwarray/Copyright Agency

* “Country” is a colloquialism of Aboriginal English that means culturally inherited track of land bound to specific understanding of abiding spirituality and of being in and out of the country. Possession is collective where humans are linked by kinship bonds. It contains everything. It’s humans, land, and the relationship between them. 11

** The Dreaming refers to the creation period when shape-shifting ancestors forged features of the landscape such as rockholes, sand dunes, mountain ranges, and bodies of water. On epic journeys, these beings named the landscape, enshrined its ritual and ecological laws, and handed down the appropriate behavioral values. The ancestors subsequently transformed into many of the unique plants and animals that live and grow on the continent of Australia or metamorphosed into the ancestrally created landscape, vesting it with their sacred power.

The landscape is thus understood to hold the evidentiary traces of these sacred things, their invocation by Aboriginal people during ceremonial productions, artistic undertakings, and in everyday life animates and activates this ancestral power.” 12

Images:

© Emily Kam Kngwarray/Copyright Agency Photo: Damian Griffiths, courtesy Pace Gallery

FOOTNOTES:

1. Merlino, Vanessa. Emily Kam Kngwarray. Everything. D’Lan Contemporary, 2023, p.5

2. Merlino, Vanessa. Emily Kam Kngwarray. Everything. D’Lan Contemporary, 2023, p.5

3. Merlino, Vanessa. Emily Kam Kngwarray. Everything. D’Lan Contemporary, 2023, p.8

4. Gilchrist, Stephen. Encountering Spiritual in Contemporary Art: The Presence and the Promise of the Ancestors. Spirituality in Australian Aboriginal Art. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2018, p.148

5. Merlino, Vanessa. Emily Kam Kngwarray. Everything. D’Lan Contemporary, 2023, p.6

6. Gilchrist, Stephen. Encountering Spiritual in Contemporary Art: The Presence and the Promise of the Ancestors. Spirituality in Australian Aboriginal Art. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2018, p.145

7. Gilchrist, Stephen. Encountering Spiritual in Contemporary Art: The Presence and the Promise of the Ancestors. Spirituality in Australian Aboriginal Art. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2018, p.148

8. Gilchrist, Stephen. Encountering Spiritual in Contemporary Art: The Presence and the Promise of the Ancestors. Spirituality in Australian Aboriginal Art. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2018, p.143

9. Gilchrist, Stephen. Encountering Spiritual in Contemporary Art: The Presence and the Promise of the Ancestors. Spirituality in Australian Aboriginal Art. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2018, p.144

10. Merlino, Vanessa. Emily Kam Kngwarray. Everything. D’Lan Contemporary, 2023, p.8

11. Gilchrist, Stephen. Encountering Spiritual in Contemporary Art: The Presence and the Promise of the Ancestors. Spirituality in Australian Aboriginal Art. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2018, p.143

12. Gilchrist, Stephen. Encountering Spiritual in Contemporary Art: The Presence and the Promise of the Ancestors. Spirituality in Australian Aboriginal Art. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2018, p.143